Why humanitarian aid works as an outpost of empire, and how mutual aid sustains survival in Palestine, Sudan, and Congo.

Introduction

On social media, Palestinians risk everything to livestream their own destruction. Phones held up in Gaza broadcast homes turned to rubble, children rescued from dust, and the sounds of warplanes overhead. However, Meta Platforms throttle, silence, or erase these livestreams. Moreover, officials tell the world that humanitarian aid is coming, that the global community is responding, while the Israeli government holds up convoys, blocks trucks at the border, and lets supplies rot or be diverted. As a result, Palestinians livestream genocide while the promised lifeline never arrives.

Meanwhile, in Sudan, armed RSF militias drive women to mass suicide, forcing them to choose death over the certainty of sexual violence. These militias abduct children and sell them into slavery, treating their lives as commodities. Instead of isolated tragedies, these patterns reveal systemic violence in a world where “humanitarian aid” is absent, withheld, or weaponised.

At first glance, many people imagine humanitarian aid as compassion in action—neutral, benevolent, and offered as a lifeline in the face of disaster. The term evokes convoys of food, medical supplies, clean water, blankets, and the comforting belief that the world does not abandon the vulnerable. In reality, aid is rarely neutral. It is conditional, surveillant, and political.

Furthermore, state-backed NGOs and international institutions often step into crises not to dismantle the systems causing dispossession but to manage them instead. The very governments that fund these organisations are often the same ones arming occupations and waging wars. Aid becomes another theatre of control, one that sorts people into categories of “deserving” and “undeserving,” keeping survival contingent on donor approval and international optics.

Ultimately, this system produces double violence. First, occupying forces displace, starve, assault, and enslave communities. Then, when survivors turn to the world for help, aid systems track, catalogue, and discipline them. Survivors must prove their suffering in donor-friendly terms; their dignity shrinks into line items on an accountability report. Therefore, humanitarian relief often enforces “chronic temporariness”—a perpetual state of limbo that keeps people alive but never free.

In contrast, out of this machinery of harm, something different emerges: mutual aid. When institutions abandon them, people turn to one another. Palestinians reaching out via social media—risking their dignity in capitalist platforms—prompt many in the US and Europe to start crowdfunding on their behalf through platforms such as GoFundMe or Chuffed. Likewise, in Sudan, volunteers deliver food where aid agencies retreat. In Congo, communities build survival networks against centuries of extraction. These are not acts of charity but of solidarity. Mutual aid is survival work that refuses the hierarchies of donor and recipient. It restores the redistributive ethic that state-run charities and global NGOs have hollowed out.

Against this evidence, this essay traces how humanitarian aid has become a tool of empire; how Palestinians, Sudanese, and Congolese expose its failures; how the states co-opted Islam’s zakat and sadaqah into bureaucratic spectacle; and why mutual aid matters as the humane alternative. To understand this fully, we must set aside the comforting myth of aid as compassion and recognise instead the systems of power it sustains.

1. Humanitarian Aid as Power, Not Neutrality

Governments, NGOs, and media portray humanitarian aid as benevolent and neutral, framing it as an indispensable lifeline for communities in crisis. Yet, when examined more closely, it becomes clear that aid is deeply entangled with systems of power. Large NGOs, global financial institutions, and state donors rarely operate with neutrality; political and economic interests shape their actions. They operate within geopolitical and economic structures that serve the interests of empire rather than the survival or dignity of dispossessed communities. The language of relief obscures this reality, but the evidence appears everywhere: in how aid distributors selectively allocate resources, in the conditions donors attach to delivery, and in the optics organisations use to justify continuing their work.

A. NGOs and Empire

Too often, NGOs present themselves as independent humanitarian actors. In practice, most large NGOs depend heavily on donor states and international institutions for funding, which shapes their priorities and limits their autonomy (Feldman, 2007). They are rarely neutral. For example, the United States sends billions of dollars annually in military aid to Israel while simultaneously funding NGOs that operate in occupied Palestine. This contradiction is not accidental. It reveals a structural logic: states deploy aid not to liberate Palestinians but to manage the humanitarian consequences of U.S.-backed occupation and dispossession.

This phenomenon is not unique to Palestine. Across the Global South, donors pressure grassroots movements to conform to their expectations in order to sustain financial viability. What began as radical resistance risks becoming “NGO-ised”—hollowed out by project-based funding cycles, monitoring requirements, and the need to appear apolitical in order to secure grants (Choudry & Kapoor, 2013). Grassroots organising loses its sharper edges not for lack of resistance, but because the donor economy discourages defiance while rewarding compliance.

B. Disaster as Marketplace

Antony Loewenstein (2015) describes this global pattern in Disaster Capitalism, where crises are transformed into profitable markets. In places like Afghanistan, Haiti, and Palestine, the entry of aid does not simply alleviate suffering; instead, it generates industries. Private security companies, logistics firms, construction contractors, and even NGOs themselves all carve out profit streams from humanitarian operations. Every crisis becomes an economic opportunity, a site for accumulation by external actors.

This “marketisation” of aid prevents relief from ending the underlying conditions of dispossession. Instead, aid perpetuates dependency. Food convoys are distributed while agricultural systems remain destabilised. Emergency shelters are built while housing is left in ruin. Security companies are contracted to protect aid workers, but not civilians. Rather than dismantling structural violence, humanitarian aid becomes part of the machinery that sustains it.

C. Conditionality and Surveillance

Another way aid functions as power is through conditionality. International financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank often tie loans or development assistance to structural adjustment programmes that enforce privatisation, austerity, and trade liberalisation. These measures disproportionately harm vulnerable populations while securing foreign access to markets and resources (Abouharb & Cingranelli, 2007). The language of “assistance” masks the coercion embedded in these arrangements.

Beyond economic conditionality, humanitarian aid also involves direct surveillance. Refugees and displaced people are tracked, categorised, and managed through aid programmes. Registration systems, biometric data collection, and ration cards turn survival into a bureaucratic process. Ilana Feldman (2007) describes how these practices foster dependency rather than autonomy, as recipients are compelled into cycles of verification and compliance, continually proving their eligibility for relief. Aid becomes a form of governance, disciplining populations while appearing to serve them.

This surveillance also produces knowledge that is useful to states and international actors. Refugee camps, for example, are not only sites of shelter but also laboratories for demographic data, behavioural studies, and social engineering. In this way, humanitarianism extends beyond immediate relief into long-term management of entire populations.

D. Optics Over Liberation

Humanitarian aid also thrives on optics. NGOs and international organisations rely on crisis imagery—photographs of starving children, stories of devastated families—to justify budgets and appeal to donors. Annual reports, donor conferences, and “impact metrics” become central to sustaining the aid industry. The emphasis shifts from addressing structural causes of suffering to maintaining a compelling narrative for funders.

In these systems, distrust becomes normalised. Communities learn to see one another as competitors for recognition, forced to perform their suffering in ways that will attract donor attention. Rather than fostering solidarity, aid pits communities against one another, eroding trust and interdependency. The dignity of survivors is disregarded, reduced to data points in donor-centric accountability reports.

What is obscured in these optics is liberation. Very little of humanitarian aid is aimed at dismantling the structures that produce war, occupation, or famine. Instead, the focus is on visibility: keeping crises legible to donors while ensuring that the underlying political conditions remain unchanged. This is why aid to Palestine can flow in tandem with military occupation, and why aid to Sudan can coexist with international neglect of its wars. The appearance of care matters more than ending the conditions of suffering.

2. Palestine as a Case Study in Aid-as-Control

Palestine offers one of the clearest illustrations of how humanitarian aid functions less as a lifeline than as a mechanism of control. Nowhere else is the contradiction more visible: massive inflows of aid coexist with deepening occupation, mass displacement, and the deliberate destruction of livelihoods. The aid industry here does not dismantle injustice; it sustains a managed version of Palestinian survival that relieves international guilt while securing Israeli control.

A. Donor Economics > Liberation

Sahar Taghdisi-Rad (2010) has shown how international aid to Palestine is structured around donor economics rather than Palestinian liberation. Policies such as “Aid for Trade” reframe Palestinian survival through the lens of economic development, as if the fundamental obstacle were inefficient markets rather than military occupation. These donor-driven frameworks erase the political reality of colonisation and repackage it as a technical problem.

The result is what Taghdisi-Rad (2010) calls de-development: the systematic dismantling of local economic structures under the guise of development. Palestinian industries are fragmented, agriculture is disrupted by land confiscation, and movement restrictions undermine trade. Yet donor agendas continue to prioritise economic schemes that cannot function under occupation, reinforcing dependency on external aid flows instead of building genuine self-sufficiency.

This reflects a broader pattern: international assistance is rarely designed to end structural violence. Instead, it sustains a fragile and conditional survival that leaves the roots of dispossession untouched. For Palestinians, this means that billions in aid have done little to challenge the fundamental fact of Israeli control.

B. Normalising Occupation

Anne Le More (2008) argues that international aid in the post-Oslo period (1993–2007) actively normalised the occupation. By funnelling resources through the newly created Palestinian Authority (PA), donors effectively subsidised the costs of Israeli domination. Rather than forcing Israel to end its colonial project, aid underwrote the structures that allowed it to continue.

This aid regime depoliticised Palestinian resistance by shifting the focus from liberation to governance. The PA, reliant on donor funding, was transformed into an administrative body tasked with managing Palestinians rather than liberating them. Donor money financed salaries, security forces, and bureaucracies, while Israeli settlements expanded and military control deepened. The occupation became more sustainable for Israel because its costs were externalised onto the international community.

Le More (2008) captures the paradox starkly: aid was not simply wasted; it was instrumental in stabilising the very conditions it claimed to address. The PA became authoritarian under donor pressure, policing its own people while presenting itself as a legitimate government to international funders. Resistance was reframed as extremism, while “development” became synonymous with acquiescence.

C. Chronic Temporariness

Ilana Feldman (2007; 2015) has described how humanitarianism in Palestine produces a condition of “relief time,” where life is suspended in a state of perpetual temporality. Palestinian refugees have lived for decades in camps that were never meant to be permanent. Yet humanitarian structures enforce a limbo in which people are neither entirely abandoned nor truly supported.

This chronic temporality disciplines Palestinians into a state of managed survival. Relief is provided, but always with caveats: it must be verified, documented, and categorised. Refugees are treated less as political subjects and more as humanitarian cases. Their existence is governed through files, ration cards, and biometric systems. Aid becomes a means of surveillance as much as sustenance.

Accountability mechanisms deepen this alienation. Reports and audits are designed not to centre survivors but to reassure donors. As a result, “accountability reports become donor-centric performances,” flexing transparency as an achievement while disregarding the dignity of recipients. Palestinians are reduced to data points in metrics that prove efficiency to funders but strip people of agency and voice.

D. Aid Theft and Exploitation

On top of this bureaucratic control, Palestinians face the blunt violence of aid theft and exploitation. Israeli authorities have repeatedly blocked aid convoys at border crossings, leaving supplies to rot while communities go hungry. At times, trucks are allowed through only to be intercepted by gangs who seize the goods and resell them at extortionate prices in local markets.

As The Guardian reported, medical staff in Gaza have even been forced to confront gangs fighting over humanitarian supplies, while patients are left without vital treatment (Beaumont, 2025). This grotesque process transforms humanitarian aid into a commodity on the black market. Instead of alleviating suffering, it becomes another layer of dispossession. Families who should have received flour or medicine free of charge must now pay exorbitant sums for what was meant to be relief.

The structural implication is chilling: humanitarian aid can coexist with—and even reinforce—deliberate starvation. When aid is treated as a tradable good rather than an obligation to protect life, it ceases to be humanitarian in any meaningful sense.

E. Profit Industry

These patterns illustrate Loewenstein’s (2015) wider argument in Disaster Capitalism: every layer of humanitarian relief is an industry. In Palestine, the aid system sustains not only NGOs but also contractors, consultants, smugglers, and private companies. What is presented as generosity is also a marketplace. Money flows in, but much of it circulates among intermediaries rather than reaching Palestinian families.

For international actors, Palestine becomes a site of both moral theatre and economic opportunity. Donor states can posture as compassionate while continuing to fund Israeli militarism. NGOs can expand their operations and budgets. Contractors and consultants profit from endless projects. Meanwhile, Palestinians remain trapped in dependency, their dispossession stabilised rather than dismantled.

F. Palestinians Online Today

In the face of these structures, Palestinians themselves have turned to alternative strategies. Increasingly, individuals and families reach out to people outside Palestine via social media, livestreaming their circumstances, appealing for help, and documenting their survival. This act often carries immense risks, including the erosion of dignity under a capitalist system that requires people to publicly display their suffering in order to secure aid.

These online appeals have led to supporters in the United States and Europe establishing crowdfunding campaigns on behalf of Palestinians, using platforms such as GoFundMe and Chuffed. This digital chain of solidarity is imperfect—it depends on capitalist infrastructure, it requires the translation of suffering into donor-friendly narratives, and it exposes Palestinians to surveillance and online harassment. Yet it has also become one of the only available mechanisms for bypassing the gatekeeping of states and NGOs.

This form of crowdfunding is not charity. It is desperate solidarity—a refusal to let people starve or die unseen while international aid systems fail them. It embodies the spirit of mutual aid, crossing borders to meet urgent needs, even while acknowledging the limitations of the platforms that host it.

…

Palestine demonstrates with painful clarity that humanitarian aid is never neutral. Donor economics erase occupation, aid regimes normalise colonial control, and humanitarianism enforces chronic temporariness. Aid is stolen, commodified, and turned into profit while Palestinians are forced into cycles of humiliation and dependency. And yet, Palestinians continue to resist—not only through political struggle but also by reshaping how survival itself is organised.

From relief camps to crowdfunding platforms, Palestinians expose the contradictions of humanitarianism and point toward a different future. The lesson is unmistakable: aid that is tied to empire will always sustain dispossession. Mutual aid, by contrast, builds solidarity across borders, refuses donor hierarchies, and insists on dignity as non-negotiable.

3. Why Mutual Aid Is Different

Humanitarian aid operates through hierarchies—donors and recipients, funders and beneficiaries, managers and the managed. Mutual aid, by contrast, disrupts those hierarchies. It is not charity but collective survival. It is not administered from above but practised horizontally among those who share risk and need. Dean Spade (2020) describes mutual aid as both survival work and political education: meeting urgent needs while teaching communities how to resist the systems that produced those needs in the first place.

A. Dean Spade’s Framework

At its heart, mutual aid insists that communities can and must care for one another outside the state and the market. Unlike humanitarian aid, which positions survivors as passive recipients, mutual aid recognises them as active participants in their own survival. Spade (2020) emphasises three principles that distinguish mutual aid from charity:

- Collective survival and political education: Mutual aid sustains life in crisis while also raising consciousness about systemic injustice.

- Refusal of donor hierarchies: Relationships are horizontal, not defined by who gives and who receives.

- Survivor-centred accountability: Communities hold themselves responsible to each other, not to external donors or states.

In this framework, trust becomes the currency. People rely on one another because they must. When institutions fail or actively abandon them, networks of mutual aid emerge to fill the gap, not by replicating bureaucracy but by weaving solidarity.

B. Principles of Mutual Aid

Mutual aid functions through decentralisation and participation. It is built on small, distributed efforts that are flexible, responsive, and locally accountable. Because it does not rely on professionalised aid workers or donor contracts, mutual aid can adapt quickly to changing circumstances.

This horizontality distinguishes it from humanitarianism. Where NGOs demand endless reports and metrics, mutual aid depends on trust, relationships, and reciprocity. Where humanitarianism encourages pity — a donor’s compassion for the unfortunate — mutual aid cultivates solidarity, the recognition that everyone’s survival is bound together.

Moreover, mutual aid refuses to separate immediate needs from systemic critique. Food distribution, shelter provision, or medical care are not treated as isolated tasks but as part of a broader struggle against the structures producing hunger, homelessness, or dispossession. As Spade (2020) notes, mutual aid “exposes the failures of systems while simultaneously meeting people’s needs.”

C. Contemporary Examples

Mutual aid in Palestine, Sudan, and Congo demonstrates how these principles take shape under conditions of war, famine, and occupation.

In Palestine, crowdfunding networks have emerged as lifelines when formal aid is blocked or stolen. Families post appeals on social media, livestreaming their survival and reaching out to the world. Because platforms like GoFundMe or Chuffed are inaccessible to many Palestinians directly, supporters in the United States and Europe often establish campaigns on their behalf. This digital chain of solidarity is imperfect — it risks humiliation, depends on capitalist infrastructure, and exposes people to surveillance — yet it represents one of the few ways to bypass the gatekeeping of NGOs and states. These campaigns are not charity; they are desperate forms of solidarity that insist Palestinians must not be left to starve in silence.

In Sudan, grassroots hubs such as the Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition(mutualaidsudan.org) have stepped in as NGOs retreat. These initiatives channel resources directly to families, bypassing donor conditionality and bureaucratic delay. Volunteers distribute food and medicine at immense personal risk, embodying the principle of survival with dignity. They demonstrate how communities can care for one another even as international actors fail them.

In Congo, Team Congo RDC teamcongordc.com provides another powerful example. Operating in a context marked by centuries of extraction and continuing conflict, it offers transparent, community-led aid that resists the exploitative logic of global humanitarianism. Rather than masking resource plunder, Team Congo RDC centres Congolese survival and self-determination.

Alongside these initiatives, digital amplification has become a critical layer of mutual aid in the present era. On Threads, campaigns circulate rapidly through a mutual aid community that translates need into action.

The WRZKY Mutual Aid Hub operates within this ecology as an amplifier, curating, archiving, and amplifying campaigns for Palestine, Sudan, and the Congo that are already circulating in mutual aid networks. Unlike on-the-ground hubs such as Team Congo or Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, WRZKY Mutual Aid Hub does not run operations directly. Its role is to extend reach, connect campaigns to broader audiences, and make them more discoverable beyond the ephemeral churn of social media. Amplification is not a replacement for organising; it is one of the ways solidarity adapts in the digital age.

Together, these examples illustrate what distinguishes mutual aid from humanitarian aid. They do not demand recipients perform their suffering for donors, nor do they reinforce hierarchies of giver and receiver. They insist instead on redistribution, dignity, and trust. Where humanitarian aid manages life as a problem of logistics, mutual aid enacts life as a practice of solidarity.

4. The Islamic Dimension: Zakat and Sadaqah

For Muslim communities, mutual aid cannot be understood apart from the religious traditions that already enshrine redistribution as a central duty. Islam places justice at the heart of its economic and social vision, and zakat and sadaqah are two of its most important mechanisms for ensuring that wealth circulates and that no one is left in destitution. These practices are not designed as acts of charity, but as systemic obligations. Yet, as with humanitarian aid, state institutions have co-opted and hollowed out these traditions, turning them into tools of legitimacy, control, and prestige.

A. Origins and Intent

Zakat is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, a compulsory redistribution of wealth intended to prevent hoarding and exploitation. The Qur’an identifies specific recipients — the poor, the indebted, the traveller, those working to collect zakat, and others in need (Qur’an 9:60). It is not an optional act of generosity but a binding duty, ensuring that resources circulate within society and that justice is enacted in material form.

Sadaqah, by contrast, is voluntary almsgiving. It extends the principle of zakat beyond obligation, encouraging Muslims to give freely and regularly. Like zakat, sadaqah treats wealth as God’s trust and requires Muslims to share it to protect community wellbeing. Both practices reject the individualism of wealth-hoarding and affirm interdependence, recognising that one person’s survival depends on everyone else’s.

Historically, Muslim communities used zakat and sadaqah as mechanisms of social security. They ensured that society protected orphans, widows, and marginalised people instead of abandoning them. They practised redistribution, not pity, and they grounded this practice in the belief that communities must live justice collectively and not merely preach it.

B. Co-optation by States

In many Muslim-majority countries today, the state has bureaucratised and captured the radical potential of zakat and sadaqah. Zakat bureaus and state-run charities turn a community obligation into a centralised project they manage from above. These institutions often operate less as engines of redistribution and more as prestige projects for regimes, used to burnish their legitimacy at home and abroad.

In practice, instead of empowering people experiencing poverty, the state frequently channels zakat funds into large-scale infrastructure or symbolic projects designed to showcase state benevolence. Moreover, elites launder wealth through zakat institutions, fulfilling the letter of obligation while betraying its spirit. As such, recipients are stratified into hierarchies, with some deemed more “deserving” than others. In effect, this mirrors the logic that plagues humanitarian aid: a hierarchy of grief in which the value of lives depends on political convenience. Notably, in some contexts, this stratification echoes fascist logics, disciplining who may receive compassion while excluding or stigmatising others.

Consequently, this co-optation reduces zakat and sadaqah from tools of justice into spectacles of piety. In turn, the act of giving becomes an instrument of control, a way for states to display power, secure loyalty, and reinforce economic hierarchies rather than dismantle them.

C. Hollowing Out of Spirit

The consequences of this co-optation are profound. What remains of zakat and sadaqah in these institutionalised forms is only the shell. The spirit of solidarity — the insistence that no one should be abandoned—is hollowed out. In its place is a bureaucratic process that mirrors the surveillance and donor-centric logic of humanitarian NGOs.

State institutions force zakat recipients into categories and reduce their dignity to eligibility criteria. They turn a daily obligation of redistribution into a distant, centralised transaction. As with international aid, the process often cultivates dependency rather than empowerment, replacing trust and solidarity with suspicion and competition. Communities learn to see one another not as co-survivors but as claimants contending for limited resources.

This transformation undermines the radical ethic embedded in Islam: that wealth is never private property alone, but always bound by the claims of others. When institutions bureaucratise zakat, it no longer embodies its ethic. It becomes another form of institutional control, hollow in substance and compromised in purpose.

D. Grassroots Contrast

Inside this hollowed-out system, grassroots mutual aid embodies the original intent of zakat and sadaqah more faithfully than many state institutions. Informal networks of giving, neighbourhood collections, and digital campaigns in the Threads mutual aid community continue the tradition of redistribution as survival.

When Palestinians crowdfund to evacuate families from Gaza, or Sudanese hubs deliver food directly to displaced communities, or Congolese organisers sustain families amidst war and extraction, they enact the true spirit of sadaqah and zakat. These acts are not charity but collective obligation: a refusal to abandon one another in the face of structural violence.

In this sense, mutual aid is not an innovation imposed from outside Islamic tradition, but a continuation of its most radical core. It represents the living sadaqah and zakat: redistribution, survival, and dignity, practised horizontally and without the mediation of state bureaucracy.

By reclaiming these traditions from state capture, mutual aid networks affirm that justice is not a prestige project or a donor metric. It is the everyday work of survival, rooted in solidarity and lived faith.

5. Sudan: Where Contradictions Converge

Sudan reveals in devastating clarity that foreign aid is not a lifeline but an outpost of empire. Aid agencies embed surveillance, enforce dependency, and retreat when conditions become too dangerous. What remains are community-led networks that prove survival is always possible outside donor gatekeeping. In Sudan, the Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) of the Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition have become lifelines—efficient, transparent, and accountable to the people they serve, not to distant donors.

A. The Crisis

Since the outbreak of fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2023, the country has been plunged into escalating violence. Darfur, Al Jazirah, and Khartoum have become epicentres of famine and displacement. In North Darfur, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) declared famine in 2025, with acute malnutrition reaching 40% among children under five (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025b). Camps such as Zamzam and Abu Shouk witnessed mass killings and starvation, while RSF forces attacked villages and abducted civilians.

Basic infrastructure has collapsed. Over 70% of health facilities are non-functional, while cholera outbreaks and power shortages cut off access to clean water and medicine. Agriculture in Al Jazirah—once Sudan’s breadbasket—has been gutted. Irrigation canals have dried, and families have abandoned their farms, leaving the country on the brink of total food collapse (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025b).

International humanitarian agencies, far from being neutral lifelines, have retreated. In March 2025, USAID suspended its programmes, halting health, food, and protection projects. Other international NGOs scaled down or withdrew after attacks on convoys and the looting of warehouses. The suspension of foreign aid did not reveal a void of generosity; it exposed its true nature. Donors built surveillance infrastructures to manage populations, not empower them. They manufactured dependency, and when empire withdrew, it left devastation behind.

B. Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition

In this vacuum, Sudanese communities organised for themselves. The Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition (mutualaidsudan.org) mobilises Emergency Response Rooms: decentralised, volunteer-led hubs embedded in local communities. ERRs operate community kitchens, distribute food baskets, run mobile clinics, and install water systems. They operate without donor bureaucracy, relying instead on deep trust and a thorough understanding of local needs.

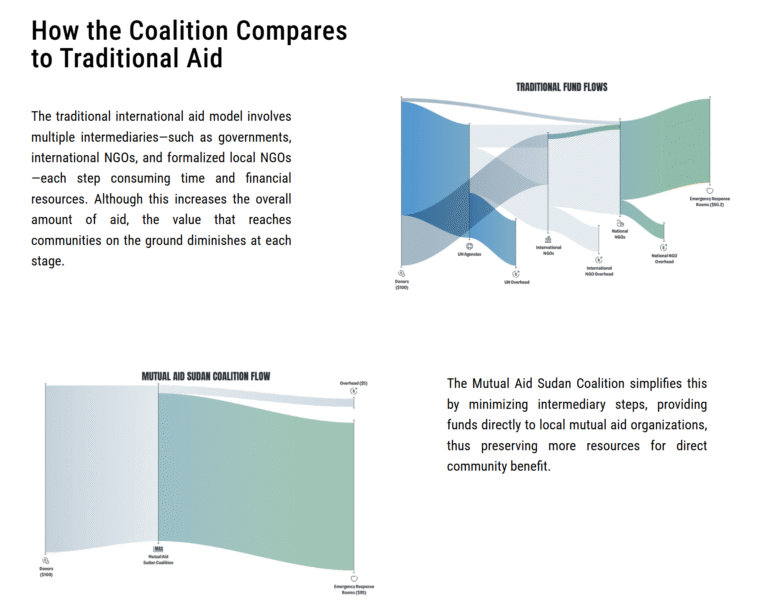

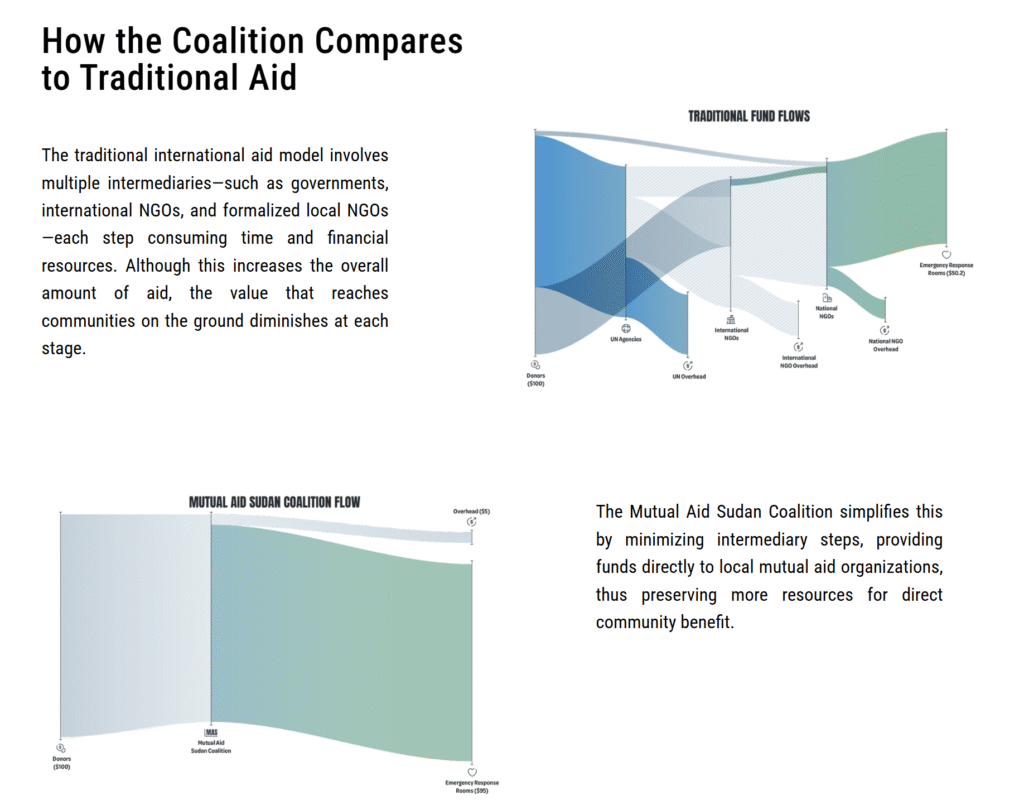

The Coalition makes clear how different this model is from traditional aid. In the international system, donor money flows through multiple intermediaries—UN agencies, international NGOs, national NGOs—each layer consuming resources and time before a fraction of the funds reach communities. By the time $100 of donor funds trickle down, barely $50 makes it to the people on the ground (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025a). ERRs bypass this chain entirely. Money flows directly to communities, where they spend it transparently and immediately. There are no bureaucratic bottlenecks, no donor-centred reporting cycles, only survival with dignity.

The results are striking. According to the Coalition’s Legatum Foundation report, between March and May 2025, ERRs disbursed $215,000 to 36 activity plans across 12 states, reaching 185,182 people. The average cost per individual was just $1.16—a fraction of what international agencies spend (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025b). Projects ranged from nutrition screening and emergency feeding in famine zones to mobile health clinics in bombed-out villages to six solar-powered water pumps in Al Jazirah that restored clean water for over 16,000 people. Communities themselves contributed labour and in-kind support, showing that solidarity, not foreign aid, sustains life.

Fundamentally, Emergency Response Rooms embody Dean Spade’s (2020) framework of mutual aid. They refuse donor hierarchies, centre accountability to survivors, and operate on trust rather than surveillance. In this regard, their integrated responses that include food, health, water, and protection resist the fragmented, professionalised logic of NGO interventions. Likewise, they practice the redistributive intent of zakat and sadaqah in Islam as justice rather than charity. At the same time, unlike state zakat bureaus or donor-controlled projects, ERRs live these principles horizontally: those who have little share with those who have nothing.

Importantly, the risks are immense. ERR volunteers face violence, raids, and death. In North Darfur, three volunteers were killed during attacks on food distributions. In Umm Kadada, RSF militias looted food baskets and destroyed supplies (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025b). Even so, ERRs persist, adapting through clandestine deliveries, split shipments, and community ingenuity. Consequently, their resilience proves that decentralisation is not fragility but strength.

…

Sudan demonstrates that foreign aid is not a lifeline but empire’s outpost. Its suspension revealed what was already true: international aid entrenches dependency, monitors populations, and abandons them when political risk rises (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025b). In many instances, Sudanese communities rather than UN agencies or donor governments secure survival today through a grassroots coalition that redistributes resources with efficiency and dignity.

Taken together, the Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition demonstrates a different future. It shows a world where aid bypasses surveillance infrastructures and flows directly to communities. In practice, the Coalition is Sudanese people organising for themselves and proving that mutual aid is not theory but practice. It is survival work that embodies both Spade’s radical framework and the Qur’anic ethic of redistribution. Where empire withdraws, Sudanese solidarity endures.

6. Congo: Another Living Example

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) illustrates with brutal clarity how humanitarian aid operates as a mask for exploitation. For centuries, Congo has been a site of extraction—first through slavery and colonial plunder, and today through the mining of cobalt, coltan, and other minerals that power the global technology industry. Wars have repeatedly erupted in eastern Congo, fuelled by competition over these resources. Each new round of conflict produces fresh waves of displacement and devastation, while multinational corporations and foreign powers continue to profit.

A. Historical Exploitation

Congo’s history cannot be separated from its resources. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, King Leopold II of Belgium presided over one of the most violent colonial regimes in history, extracting ivory and rubber through a system of forced labour that killed millions. Following formal independence, colonisers did not end plunder. They replaced it with neo-colonial economic arrangements that keep Congolese resources flowing outward.

In the present, Congo supplies the majority of the world’s cobalt, a mineral essential for lithium-ion batteries used in smartphones, laptops, and electric cars. At the global level, multinational corporations rely on Congolese mines to sustain “green” technologies marketed in the Global North, even as child labour, toxic conditions, and violent competition mark these mines. Armed groups in North Kivu and Ituri exploit and tax these industries, while foreign companies profit from cheap extraction. As a result, war, displacement, and hunger are not aberrations in Congo; they are the structural consequences of global demand.

B. Aid and NGOs

Within this ongoing history of extraction, humanitarian aid functions less as relief than as a management tool. International NGOs are highly visible in eastern Congo, yet their presence does not challenge extraction or war. Instead, aid manages poverty, providing limited services to displaced populations while leaving resource exploitation intact. Camps around Goma have swelled with over a million internally displaced people (IDPs). Nevertheless, conditions remain catastrophic: tens of thousands share a few dozen latrines, health infrastructure is absent, and sexual violence is widespread (Team Congo RDC, 2024).

Consequently, the logic is familiar. Aid provides just enough support to keep people alive, but not enough to change the structures that force them into camps. Humanitarian organisations present themselves as lifelines while the underlying violence of resource plunder, armed conflict, and political corruption continues unchecked. In effect, aid stabilises exploitation rather than dismantling it, ensuring that the global supply of cobalt and coltan remains uninterrupted.

C. Team Congo RDC

Amid this landscape of extraction and neglect, Team Congo RDC has emerged as a grassroots initiative committed to transparency, dignity, and survival. Unlike international NGOs, it functions outside donor bottlenecks and bureaucratic cycles. It is community led, lean, and accountable to the people it serves.

According to its 2024 mission report, Team Congo RDC focused its interventions on three displacement camps in Goma: 8th CEPAC Mugunga, DGDA Mugunga, and Don Bosco. Dire conditions mark these camps. In one case, 44,000 people shared just 50 latrines, creating a hotbed of cholera and waterborne disease. Another camp, Lushagala, with 400,000 residents, had no functional health infrastructure. Food aid had not reached Don Bosco and EP Patemo camps since October 2023, worsening acute malnutrition. Beyond these material shortages, the camps are sites of trauma: over 250 women reported sexual assaults in Mugunga, and a May 2024 bombing killed 35 people, including 26 children (Team Congo RDC, 2024).

In response, Team Congo’s interventions in November 2024 included:

- 298 mobile clinic consultations across the camps.

- 195 individual packages of food and essential goods.

- Porridge for 250 children, addressing acute malnutrition.

- Psychosocial support for 86 survivors of sexual violence, explosions, and massacres.

- A day trip for displaced children to Goma stadium, restoring a sense of joy and dignity amidst trauma.

In total, the mission reached 918 direct beneficiaries with limited resources. Over 85% of funds raised—mainly through a GoFundMe campaign totalling $10,477—were spent directly on humanitarian assistance, with minimal overhead (Team Congo RDC, 2024). Planned projects for 2025 include constructing 100 new latrines, creating temporary education centres for 50,000 displaced children, doubling beneficiaries to 1,500, and establishing permanent psychosocial centres for survivors.

What distinguishes Team Congo is not scale but orientation. Its work is embedded in communities, transparent in reporting, and committed to dignity as much as survival. In doing so, it demonstrates that mutual aid can function even in conditions long dominated by foreign NGOs. By mobilising funds directly and delivering them without layers of bureaucracy, Team Congo RDC bypasses the structures that consume resources in the traditional aid economy.

…

Congo demonstrates that humanitarian aid does not exist apart from exploitation, but it coexists with it, masking the violence of resource plunder while managing displaced populations. Yet initiatives like Team Congo RDC show another path. By operating transparently and directly, they provide survival with dignity, proving that mutual aid is possible even in one of the world’s most exploited and abandoned regions. Their work echoes the same lesson Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition and Palestinian crowdfunding have taught: where empire’s aid entrenches dependency, grassroots mutual aid sustains life.

7. Toward a Humane System

Across contexts as different as Palestine, Sudan, and Congo, the same pattern emerges: humanitarian aid tied to states and international institutions functions as an outpost of empire. It surveils, manages, and disciplines populations while leaving the roots of dispossession intact. Zakat and sadaqah, meanwhile, are too often captured by states and turned into prestige projects. What is lost in both cases is the core ethic: solidarity, dignity, and redistribution. Mutual aid reclaims this ethic. It is not charity, not bureaucracy, not surveillance. It is the building of humane systems in the ruins of empire.

A. Naming the Contradiction

The contradiction is stark. Humanitarian aid, despite its name, is not humanitarian. It is tied to the foreign policy interests of donor states. It is conditional, surveillant, and depoliticising. For example, in Palestine, aid has normalised occupation, subsidising Israeli control while disciplining refugees into chronic temporality (Feldman, 2015; Le More, 2008). Furthermore, in Sudan, USAID and other donors embedded dependency only to retreat when war made conditions too unstable, exposing their role as empire’s outposts (Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition, 2025b). Likewise, in Congo, international NGOs manage displacement in overcrowded camps while resource plunder continues for the benefit of global markets (Team Congo RDC, 2024).

Similarly, religious obligation has fared no better under state capture. Zakat and sadaqah, meant to redistribute wealth as justice, have been hollowed into bureaucratic functions. In particular, states use zakat bureaus as legitimacy tools, laundering elite wealth while enforcing hierarchies of who is “deserving” of aid. Consequently, religious charity under state control mirrors the same fascistic logic as international humanitarian aid: compassion becomes stratified, dignity becomes conditional, and redistribution becomes subordinated to power.

All of this reveals, the shared contradiction is unavoidable. In both cases, secular and religious institutions transform solidarity into spectacle. Additionally, both substitute metrics, prestige, and donor confidence for the lived needs of communities. Both deny dignity.

B. Mutual Aid as Reclamation

Mutual aid offers a reclamation of what both empire and state have stripped away. As a result, it becomes what Dean Spade (2020) calls survival work that also functions as political education. Moreover, it restores accountability to where it belongs: between communities themselves. Furthermore, it builds trust as currency and insists that redistribution is an obligation we owe each other, not a favour granted by elites.

For instance, in Palestine, crowdfunding campaigns for evacuation or medical care embody this reclamation. They bypass the gatekeeping of UN agencies and state donors, creating chains of solidarity that refuse to let people die unseen. Similarly, in Sudan, Emergency Response Rooms distribute food, medicine, and water directly to their neighbours, maintaining transparent accounts and minimal overhead. Likewise, in Congo, Team Congo RDC directs 85 percent of its funds straight to displaced families, providing clinics, food, and psychosocial support outside international NGO bottlenecks.

In truth, these practices are not minor supplements to “real aid.” They are the real aid. They reclaim the spirit of zakat and sadaqah as collective redistribution rather than bureaucratic obligation. Ultimately, they show that humane systems are possible: systems where survival is not conditional, dignity is not negotiable, and justice is measured by lives sustained rather than reports submitted.

C. Digital Solidarity

In the digital age, mutual aid has taken on new forms. On the one hand, crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe or Chuffed are capitalist infrastructures that reproduce many of the same problems as donor-driven aid: they demand performances of suffering, extract fees, and expose the dispossessed to surveillance. On the other hand, they have also become indispensable tools. At the same time, Palestinians livestreaming their destruction, Sudanese volunteers sharing appeals, and Congolese organisers posting campaign links all bend these tools toward survival. As a result, digital infrastructures become unlikely spaces where dispossessed communities fight to stay alive.

Nevertheless, digital solidarity is imperfect, but it is real. Consequently, campaigns amplified on platforms like Threads extend reach beyond the limits of geography. They allow dispossessed communities to build transnational networks of care, even as states and empires attempt to block resources at borders. For example, the WRZKY Mutual Aid Hub functions as an amplifier, curating and archiving campaigns already circulating in mutual aid communities and ensuring that urgent needs do not vanish in the churn of social media. In doing so, digital platforms are retooled from sites of capitalist extraction into infrastructures of solidarity.

Therefore, the lesson is not that digital tools solve dispossession. They do not. Instead, they reveal the creativity of communities that refuse to wait for institutions that have already abandoned them. Ultimately, digital solidarity, like ERRs in Sudan or grassroots hubs in Congo, embodies the same ethic: survival through mutual responsibility.

…

To move toward a humane system requires rejecting the false promise of humanitarian aid and reclaiming the true intent of redistribution. Empire’s aid surveils and disciplines; state zakat bureaucracies legitimise power. Both hollow out solidarity. Mutual aid reclaims it.

Palestinians crowdfunding survival, Sudanese ERRs feeding their neighbours, Congolese organisers providing clinics and dignity—these are not anomalies. They are the seeds of humane systems that already exist, and they show that solidarity is not charity, justice is not a spectacle, and survival is not something to be negotiated by donors

Ultimately, the task ahead is not to improve humanitarianism but to abandon it as a model. To stand with Sudan, Palestine, and Congo means refusing complicity in systems that profit from suffering, and committing instead to mutual aid: solidarity as survival, dignity as redistribution, justice as everyday practice.

Conclusion

To begin with, the evidence is overwhelming. Humanitarian aid, as it is practised today, is neither neutral nor designed to dismantle suffering. It is tied to empire, functioning as a tool of surveillance and discipline. Moreover, it moves through states, NGOs, and bureaucracies that consume resources, impose hierarchies of deservingness, and normalise dispossession. Likewise, the same logic extends to zakat and sadaqah. When state institutions capture them, they hollow these obligations into prestige projects and strip them of their radical intent as instruments of justice and redistribution.

Therefore, confronting this reality requires clarity. For this reason, we cannot donate uncritically; we must recognise the politics of aid. We must ask who sets the terms and whose interests are being served. When money moves through international aid chains, it strengthens systems of control. When religious obligation becomes bureaucratised, it legitimises states rather than liberating people. Both deny dignity to the communities they claim to serve.

In theory, zakat would function as Islam intends, a humane system of redistribution where wealth circulates, poverty ends, and no one is abandoned. However, we do not live in that world. Consequently, state machinery absorbs institutionalised zakat, hollows it into bureaucracy and prestige projects, and reshapes it into something that resembles international NGOs. What was meant as justice has been reduced to charity under another name.

In response, and as a result of these failures, mutual aid emerges as the most humane alternative available. It is imperfect, vulnerable, and often improvised, but it is real. Mutual aid across Palestine, Sudan, Congo, and many other contexts becomes the infrastructure of survival.

For example, in Palestine, crowdfunding campaigns for evacuations and medical care bypass the gatekeeping of UN agencies and donor governments. They expose the humiliation of displaying suffering on capitalist platforms, yet they sustain lives that institutional aid abandons. Similarly, in Sudan, Emergency Response Rooms provide food, medicine, and clean water with transparency, efficiency, and dignity, reaching more people with fewer resources than foreign aid ever could. Likewise, in Congo, Team Congo RDC directs funds straight into camps, delivering mobile clinics, food, and psychosocial support, with more than 85 percent of donations reaching people directly.

Additionally, digital amplification has become essential. In practice, platforms like the WRZKY Mutual Aid Hub keep campaigns circulating in the Threads mutual aid community visible and accessible, extending their reach beyond the churn of social media. Amplification does not replace organising; it strengthens the web of solidarity and helps meet urgent needs.

Ultimately, these practices are not charity or donor projects. They are survival work reclaimed by communities, work that restores the dignity stripped away by international humanitarianism and state zakat bureaucracies. This survival work reminds us that redistribution is not optional, justice is not spectacle, and solidarity is unnegotiable.

Thus, to stand with Sudan, Palestine, and Congo is to reject systems that profit from suffering and to choose mutual aid instead—the practice of survival, dignity, and justice in a world that has abandoned its obligations.

References

Abouharb, M. R., & Cingranelli, D. L. (2007). Human rights and structural adjustment. Cambridge University Press.

Beaumont, P. (2025, June 29). Medical staff struggle as gangs fight over aid supplies in Gaza. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/29/medical-staff-struggle-gangs-fight-aid-supplies-gaza

Choudry, A., & Kapoor, D. (Eds.). (2013). NGOization: Complicity, contradictions and prospects. Zed Books.

Feldman, I. (2007). The Quaker way: Ethical labour and humanitarian relief. American Ethnologist, 34(4), 689–705. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2007.34.4.689

Feldman, I. (2015). Life lived in relief: Humanitarian predicaments and Palestinian refugee politics. University of California Press.

Le More, A. (2008). International assistance to the Palestinians after Oslo: Political guilt, wasted money. Routledge.

Loewenstein, A. (2015). Disaster capitalism: Making a killing out of catastrophe. Verso Books.

Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition. (2025a). Coalition. Mutual Aid Sudan. https://www.mutualaidsudan.org/coalition

Mutual Aid Sudan Coalition. (2025b). Legatum Foundation report. Mutual Aid Sudan. https://www.mutualaidsudan.org/reports/legatum-foundation-report

Qur’an. (n.d.). The Holy Qur’an. (Original work published ca. 610–632 C.E.)

Spade, D. (2020). Mutual aid: Building solidarity during this crisis (and the next). Verso Books.

Taghdisi-Rad, S. (2010). The political economy of aid in Palestine: Relief from conflict or development delayed? Routledge.

Team Congo RDC. (2024). Mission report 2024. https://www.teamcongordc.com/

© WRZKY 2025

Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.

You may share this work with proper credit.

Commercial use and modification are not permitted.

🔗 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/